Ask a Battle of Atlantic Survivor: Q&A with Peter Chance

By Lookout on May 01, 2019 with Comments 2

Peter Mallett, Staff Writer ~

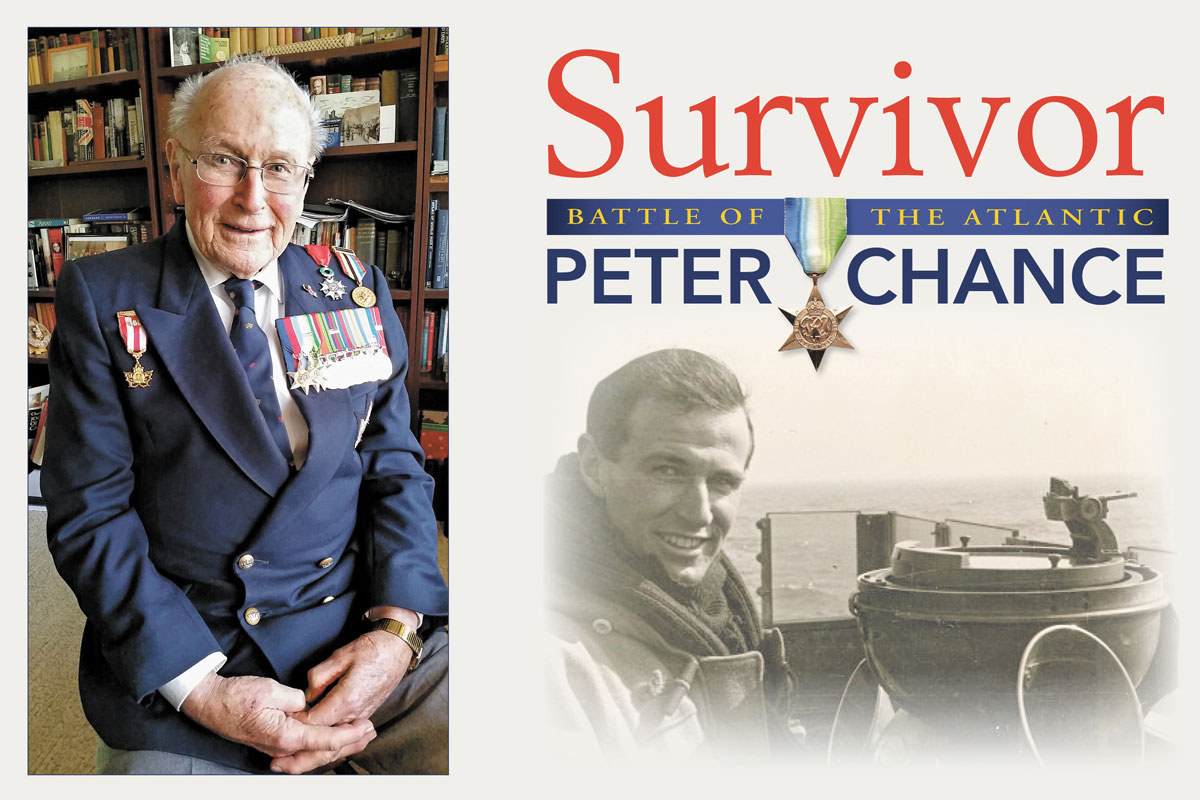

During the Second World War, Commander (Retired) Peter Godwin Chance served in a variety of Canadian warships including HMCS Skeena, HMCS Seacliff, and HMCS Gatineau.

After the war, he would see combat again as part of Canada’s support of UN operations in the Korean War. From April 1951 to July 1952 he served aboard tribal-class destroyer HMCS Cayuga, overseeing navigation and air direction during bombardments along the coastline.

In 1986, he was awarded and the Admiral’s Medal and then in 2002 the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal; in 2014 he received the French Legion of Honour Medal at the rank of Knight and was also awarded a Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation.

Today, Chance delights at the opportunity to share his vivid descriptions about his experiences at sea. His autobiography entitled, A Sailor’s Life 1920 to 2001, was published by SeaWaves Books in 2011.

Commander (Retired) Peter Godwin Chance, 98, answered some questions from today’s sailors about his service, and survival, on the Atlantic Ocean during the Battle of the Atlantic.

—

CPO2 Joe Dagenais, Chief Boatswain Mate HMCS Regina

Q: Sir, first of all thank-you for your service, and all that you and your shipmates did for Canada. My question is which of the over 40 missions that you participated in was the most memorable?

A: Operation Neptune because of the magnitude and scope, and it helped settle the course of the war.

LS Robert Thrun, Marine Systems Engineering Division HMCS Regina

Q: What were your initial reasons for enlisting in the service? Also did your personal experiences throughout the course of the war change you view point of the services or strengthen the beliefs that you already held and caused you to enlist?

A: I enlisted because my next-door neighbour in Ottawa was a Sub-Lieutenant at the local reserve division known as The Ottawa Half Company. It was 100-people strong and we did our drills in Kresge’s Department Store. Also, on my street another next door neighbour was in the reserves and across the street from him a man by the name of Commander (Retired) Edson Sherwood had served in the First World War. He had moved on to become comptroller at Government House and he was also the CO of our [reserve] division, so it seemed like a natural thing to do.

After serving in the reserves my beliefs were certainly strengthened, so when I got the opportunity at the end of 1939 to serve in the current regular force I said yes and I was then sent over to the Naval College in Dartmouth, England.

MCpl Victoria Rogers, Meteorological Technician HMCS Regina

Q: Did you get to work with many females during the time you served? If so, how was it for the males to accept having females serving with them?

A: No, I never worked with any females during the Battle of the Atlantic.

CPO2 Scott Baker, Chief Engineer HMCS Regina

Q: What was the top speed of war ships back then? How many men were in each mess for sleeping? How many days could the ship go without fuelling?

A: 31 knots; 20 men in each mess, and we could go as long as two weeks before we had to refuel.

PO2 Ka Lun Au, Financial Services Administrator HMCS Regina

Q: How often were you paid and were there any special allowances, bonuses, and what type of wages did a sailor make in those days?

A: An officer received a salary of $2 per day and non-commissioned members $1.25 – we thought it was a good deal because we had a roof and all our meals provided. We also received a $1 allowance for our mess.

Lt(N) Danielle Chagnon, Information Warfare Officer HMCS Regina

Q: During the war, what was the best way for sailors to distract themselves at sea? Were there any dull transits/exercises where skylarks were common (before WWII)? If so, what were the best/funniest things you witnessed during your time serving in the RCN? Who would you say you looked up to the most during your time in the navy? Why was this person a role model for you?”

A: A skylark is a fun game – but we didn’t have too much time for those type of things at sea. When we got on shore there were restaurants to go out to and theatre. We were in a three-watch system, four hours on eight hours off – mostly we slept. In the ships we were on watch and when you came off you were tired – you ate your meals and slept and, in the meantime, you might read or write letters home.

LS Brian Higgin, Marine Systems Engineer HMCS Regina

Q: Aside from home port, what was your most memorable port visit?

A: There were two memorable port visits for me – the most memorable was Plymouth because that is where I married my wife Margaret (Parker) Chance, but also I met her during another port visit. Me and two other sailors travelled not too far outside of Londonderry to a place called Port Rush and visited a restaurant called the Trocadero. There were three women sitting across the room from us and the shyest member of our trio took a note over to them and asked if they could come and have supper. The note asked if they were the girlfriends of soldiers; if not would they dine with us. In their note to us they replied: No we are not army R’s we are English Wrens. And yes we are hungry and so they came over to us. My future wife Peggy sat down next to me and I took one look at her and said to myself I’m going to marry her. Six weeks later we were married in Plymouth and stayed together until Peggy died in 1996.

LS Jeremey Howick , Naval Communicator HMCS Regina

Q: I was wondering what the crews did when they had a few moments to relax. When I first got into the navy, we played cards and board games a lot, now everyone seems to be glued to a television set or their computers or phones. Did you guys have a good sense of camaraderie and morale below decks? Also what was the food like on board?

A: I think the ship’s company got along very well. As an officer and navigator I was very seldom with anybody except the captain. The food all came from the same galley – there was no Cordon Bleu or beef tenderloin – it was good edible food – we were all taken care of very well and it certainly helped our spirits and morale.

LCdr Brian Henwood, Executive Officer

Q: What was the Executive Officer like on your ship? How about the Coxswain and the Captain?

A: It was me; I was the executive officer. We had a Coxswain named Greco who was a great guy. Most of the people I served with came from all walks of life and had different jobs to do before the war and all seemed to have a great sense of humour. We weren’t roaring around on board in a ‘laugh-o-rama’ but even despite the circumstances it wasn’t dead serious either. We all had a good sense of humour even though being at sea during the Battle of the Atlantic was serious business.

LS Godard, Nav Comm, CISN Op HMCS Calgary

Q: When on patrol, did you find any U-Boats? If so, what were your actions towards them?

A: Sinking German U-boats was an important job for us to do. It certainly was a case of us or them, but when we prevailed, we got the crew out and saved them because we weren’t angry with these guys. On the large scale of things, it was in fact the sea that was our real enemy. We did what we could to rescue the enemies after sinking U-boats. I still remember being put in charge of a Kriegsmarine first lieutenant and tried to speak to him in German. I was quite astonished when he interrupted my attempt to speak German and said, “Excuse me sir, I would prefer if you spoke to me in English.” I was quite disappointed because I thought it was my golden opportunity to show off my ‘Deutsch’.

When we landed with our prisoners near Clydebank [Scotland] and they were being lined up to be taken to P.O.W. camps I remember them giving us three cheers. There was a great deal of humanity considering the circumstances.

AB Killam, NCI Op, C4I Tracker HMCS Calgary

Q: What was your experience like on the HMCS Seacliffe and HMCS Gatineau after what you went through on the HMCS Skeena?

A: On HMCS Gatineau (H61) I was First Lieutenant. We did ferrying and brought troops back from the theatre of war to Canada. We opened and emptied the nest decks and put in hooks for hammocks and we brought 400 people back each time. If I remember correctly it was the German U-Boat UH77 that we assisted in sinking while we were in Sea Cliff.

OS Devine, Mar Tech, Roundsman HMCS Calgary

Q: The Battle of the Atlantic was won in the spring of 1943. The reason for this was due to large technological advancements. What major advancements did you see?

A: Improved sonar and weaponry towards the end of the war was very important. The Hedgehog was one of the newer pieces of technology; it was an anti-submarine forward throwing weapon. You would get the ship as close as you could to your contact and then when you fired it it formed a ring of bombs and that was quite effective. The Squid came along after the Hedgehog and was really something else. It had a 45-gallon drum with three barrelled mortar on the quarterdeck. When you fired that thing, you could use your sonar to get the depths of the submarine. The Squid went over the deck of the ship and using your sonar you found the target by bringing it to the surface and destroying it.

MS Bork, Mar Tech, EOOW HMCS Calgary

Q: What were the living conditions like on board?

A: Most of the ship’s company slept on hammocks underneath the bridge and fo’c’sle. When I first started my career, I once slept in a hammock over a fuel tank. When I became the navigation officer, I got my own cabin. It wasn’t much, about eight feet long and about seven feet wide – it had a bunk and a chest of drawers. It was adequate, but it certainly wasn’t luxurious.

LS Roger, WEng Tech, Radar Maintainer HMCS Calgary

Q: What is your favorite or most memorable experience during your service?

A: One of the most exciting nights was with two other ships, one was a ship called Albrighton. We were sent 10 miles off the coast of Brest, France. The name of the game was to make the German’s feel we were German naval vessels and we crept up the coast. It was well after midnight when we turned to port and flax ships came out of Brest Harbor with submarines on either side – there were three of them. As they approached, we were in position. Eventually they were 1,000 yards away and we opened up and blew them out of the water. It was either us or them. It was an assault and we prevailed; it was good and stopped the U-Boats getting into the channel and was probably the most decisive thing we ever did.

LS Vokey, WEng Tech, Jr. Weapons Engineering Tech HMCS Calgary

Q: What was the biggest challenge you faced while battling the storm for four days onboard HMCS Skeena near Reykjavik?

A: Staying alive, it was really all about survival. I can still remember how the storm was getting worse and worse with 50-foot waves. The senior officer declared we are heading into port. But I went to my captain and delicately explained to him that we can only operate one anchor at a time, and we had only one cable holder. After his insistence, I told him “I will have to ask you to relieve me of my duties as navigator, unless you order me.” He did, and I had no choice, the senior officer had ordered us in.

The captain could have said to the senior officer I would like to remain at sea, but he didn’t. So, we went in closer to shore and he said “see if you can find the best place for us to anchor.” At 800 yards from the beach in any direction I put the pick down. We veered 5.5 shackles of cable in 12 fathoms of water. As the storm raged, she held. The next thing we faced were the fierce snow squalls. The ground clutter on our radar was so bad that you couldn’t make anything out at close distance.

Then the ship began drag. As we went, the snowsqualls came up again driven by strong hurricane-force winds. We hit a point on the coastline doing about eight knots and the ship was instantly wrecked. Then a wave came up over the top of the ship and she cracked. With a cracked hull we had oil seeping up and all over the deck of the ship, and it combined with the snow to make treacherous footing. Because of the cracked hull we had to shut off the boilers and we were in pitch black. It was a very scary situation.

An order came from the bridge that said, “prepare to abandon ship”, which was taken as “abandon ship”. The waves took the first rescue boat and placed it on a high shore/high bluff and 15 of them didn’t make it. The rest of us survived, the storm went through, and the next morning we were rescued and taken ashore.

OS Ferland, Sup Tech, Storesman HMCS Calgary

Q: Can you describe your feeling when you were able to land after the ship was thrown by the storm off the coast of Reykjavik?

A: We felt we were being saved and we were. A landing craft pilot named Einar Sigurdson and a team of rescuers from Iceland rescued us and took us to the Royal Navy ships stores. We were fed and drank some rum and put into some warm blankets. We were lucky to survive.

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author:

My dad John Moss would have been on board the HMCS Skeena at Reykjavik 79 years ago (25 October 1944) when it sank but he had been told to go home to visit his mother who was very poorly. He remembered his mates waving to him as the Skeena left Plymouth saying “Bye Johnny see you at the next port” but he said he never saw them again. That was the night he lost all his good mates. He was 23 at the time and they were all similar age.

It wasn’t his time but he never forgot. He always remembered. May they Rest in Peace

These men of the Sea were very brave and served with distinction. They were of “The Greatest Generation”