Former POW recalls the Fall of Hong Kong

By Lookout on Nov 22, 2017 with Comments 0

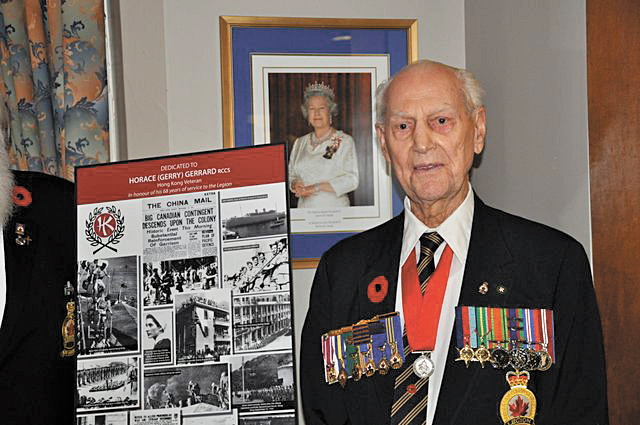

Battle of Hong Kong survivor Gerry Gerrard, 95, was the guest of honour during a plaque dedication ceremony at the Royal Canadian Legion Branch #127 on the evening of Nov. 7. The Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association dedicated a plaque in honour of Gerrard’s service to the Legion and the people of Canada during the Second World War Battle of Hong Kong. Photo by John Yankoski

Peter Mallett, Staff Writer ~

Seventy-six Remembrance Days have passed since Signalman (retired) Horace ‘Gerry’ Gerrard fought for Canada in the Battle of Hong Kong. But the memories remain.

Each year as the days of autumn grow shorter and Nov. 11 approaches, the 95-year-old recalls the Allies rapid capitulation to the Japanese, and the subsequent brutal treatment he and the other Canadian, Indian and British soldiers faced at the hands of their captors in Prisoner of War (POW) camps.

“Remembrance Day brings it all back,” says Gerrard. “In the daytime I don’t think about it much, but nights are difficult, the memories are always with me.”

The battle began Dec. 8, 1941, a day after Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan, which marked the start of war in the Pacific theatre. The fall of Hong Kong transpired in just 17 days, and during that time the Allies suffered heavy losses and turned down multiple requests by the Japanese to surrender. They finally did on Christmas Day, 1941.

Approximately 1,976 Canadians were dispatched to Hong Kong in late 1941 and more than half of them, approximately 1,050, were either killed or wounded. Of the 554

Canadians who lost their lives, 290 died during the infamous battle portion, while 264 died in its aftermath as POWs. Gerrard says the memories of the camps will remain etched in his mind until the day he dies.

“When people say it’s amazing I survived the battle, I normally tell them ‘no’, what’s amazing is that I survived my internment.”

Japan was not part of the Geneva Convention and didn’t adhere to its Treatment of Prisoners of War principles.

Legion Honours

On Nov. 7, 2017, a month ahead of the battle’s anniversary, Gerrard was honoured with the unveiling of a commemorative plaque for his 68 years of service to the Royal Canadian Legion and his role in the Battle of Hong Kong. Approximately 60 of Gerrard’s family and friends packed the front room at the downtown branch for the ceremony, organized by the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association (HKVCA).

“When I initially heard about the ceremony I thought I would be getting a medal and that is something I don’t really need,” said Gerrard. “I’m surprised how many people showed up. I’ve got to admit it, the recognition and this plaque it’s nice thing for me.”

The plaque is part of a nation-wide initiative by provincial chapters of the HKVCA to commemorate the 1,976 Canadians who fought against the Japanese Imperial Army in December 1941. They honour those who served in the war and depict the battle as part of a nation-wide initiative to help Canadians remember those who served in the often-forgotten engagement also known as The Fall of Hong Kong.

“Gerry is the last surviving member of the RCCS (Royal Canadian Corps of Signals) contingent, and one of only 14 Hong Kong veterans who were witnesses to that part of our history,” said Gerry Tuppert, HKVCA B.C. Regional Director. “The plaque will forever serve as a reminder of the sacrifices made by Gerry and his comrades during the three years and eight months of the war for them.”

The ‘Misery’ of War

Although more than three quarters of a century has passed since the Japanese annexation of Hong Kong, Gerrard is still able to provide a highly descriptive first-hand account of his Second World War experiences.

He was born in Bolton, England, on Jan. 19, 1922, but was raised in Red Deer, Alta. In 1938, at 16, he joined the town’s Reserve Artillery outfit even though 18 was the required age. The unit’s commanding officer eventually succumbed to his repeated pleading, realizing the boy’s keen interest and proficiency at Morse Code and signaling.

At the start of the Second World War he expected to be shipped overseas to the frontlines, but instead he and a group of signallers were sent out West to board RCN vessels for a voyage to Hong Kong.

As Gerrard recalls he and the rest of the Canadians “didn’t really know the misery in store” for them as they headed across the Pacific and towards a bloody battle and the spread of war in the Pacific.

As the Second Sino War raged between Japan and China a short distance away on the mainland, British command had decided to bolster the garrison to 12,000. But their attempted show of strength was little match for the strategically advantaged Japanese who numbered 50,000. They also enjoyed superiority over the Allies at sea and in the air, and had the strategic advantage in terms of resupplying and equipping their troops.

It was the job of Gerrard and the other signalmen to relay communication to and from the island’s Western Brigade back to headquarters. He says the attack by the Japanese came as a total surprise. As the first enemy war planes arrived in skies overhead, he really couldn’t understand what was happening.

“The planes overhead was the biggest threat to us, wherever you went on the island they were always watching you,” he said. “When the attack first happened, I saw a plane overhead and at first thought he was dropping leaflets, but quickly realized they were bombs because the objects he was dropping were exploding when it hit the ground.”

In the days leading up to the surrender Gerrard says he and the rest of his unit were on a heightened state of alert, constantly on edge, with very little sleep.

A Prisoner of War

He and the Grenadiers were part of the Allies last stand in Hong Kong. They tried to take the strategic position of Mount Cameron but were forced to surrender on Christmas Eve. The Canadians walked to the bottom of the hill and surrendered to the Japanese the next day.

“We were now under their control, but at first they [the Japanese] were hesitant and didn’t know how to handle us, and we didn’t know what they wanted us to do because we couldn’t understand Japanese.”

The prisoners spent their first year in captivity in an abandoned barracks in Hong Kong. They were then sent to permanent POW camps near Tokyo where they spent several months. In the final months of his captivity he moved to a forced-labour camp that operated at an iron mine in the north of the country; he spent the remainder of his days in captivity pounding metal in a blacksmithing shop.

During his three years as a POW he faced the reoccurring pain of seeing several prisoners suffer and eventually die from disease or starvation.

“It was quite pitiful and frightening to see the ones who died from starvation and their shrivelled-up bodies, these were men that I knew,” he said.

One day a POW repeatedly said “it’s over.”

“The next morning when we reported to work there were no guards present and we were all by ourselves. We got orders to stay in the camp until the Americans could liberated us a month later. They kept us alive by dropping food, medical and other supplies to us from the air.”

Gerrard was 113 pounds when he left the camp.

In December 2011, Japan officially apologized to Canadian veterans for their treatment in POW camps. The news came at the moment that Gerrard was part of a Canadian delegation visiting Sai Wan War Cemetery in Hong Kong to commemorate the battle’s 70th anniversary.

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author: