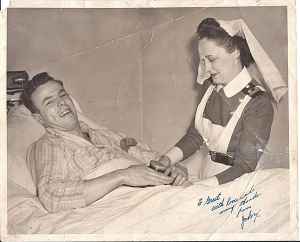

One of Canada’s first naval nursing sisters

By Lookout on Sep 08, 2015 with Comments 5

In 1943, at the pinnacle of the Second World War, Margaret “Greet” Ferguson, a graduate nurse trained in a Toronto hospital, found herself treating wounded Canadian sailors at the base in Newfoundland.

She was one among 99 other nurses chosen as Canada’s first contingent of Naval Nursing Sisters.

“I always had wanted to be a math teacher,” says Ferguson, 97.

“But my brother and I ended up being in Grade 12 together, and my dad couldn’t afford to send us both to college when we graduated at the same time, so it was proposed that I try nursing school, which was free.”

Ferguson, who grew up in the tiny hamlet of Inverness, Nova Scotia, was accepted into St. Michaels, a strict Catholic nursing hospital in the heart of bustling Toronto.

She says she still remembers the immaculate tile halls of the hospital and the scratching from her stiffly starched white collar as she worked.

“But I just kept wondering: is the war going to be over by the time I finally finish the three years of my training?”

By the end of her final year, Ferguson had accepted a position in the obstetrics ward at St. Michaels.

It was then that the Minister of National Defence, Angus MacDonald, put out a call to the country for 100 naval nurses.

Before then, nurses could only join the air force or army.

“I desperately wanted a change at that point in my life,” says Ferguson.

Minister MacDonald, once the Premier of Nova Scotia, had been born and raised in Inverness.

One phone call to MacDonald, and Ferguson found herself with a tentative offer that she might be one of the first naval nurses to serve.

“A few days after I called Angus, I got a call from a commander at the recruiting base in Toronto, HMCS York.

He said: ‘I don’t know who the heck you are, but I got a call from Ottawa to induct you.’”

Ferguson says she was thrilled.

She immediately headed for HMCS York, where she underwent a physical and was issued her uniforms.

“I stayed at that base for probably about six weeks, treating an epidemic of measles that had broken out among the sailors,” she says.

Five days a week, the Forces sent a taxi to Ferguson’s home, delivering her straight to the base to change dressings, administer medication, and hook the ill up to IVs.

But just as Ferguson had begun to fall into the routine, she was told she would be sent to a base in Newfoundland to treat the more immediate injuries of sailors harmed by German U-Boats traversing beneath the Atlantic waters.

Newfoundland was still part of the British Empire, and was classified as “overseas” to the rest of Canada.

Ferguson would be working 12 hour shifts five days a week, treating upwards of 20 injured troops a night.

“We were thrown right into it,” she says. “And you had every type of injury there: broken bones, swollen jaws, ear problems, diseases.”

“You never panicked,” she adds. “You just dealt with it.”

From sullen German prisoners to sailors feigning sick, Ferguson says she saw it all.

“I remember one man specifically, who wanted out of the navy. He would get into a wheelchair and roll down the corridors sweeping the floor. He’d tell people he was sweeping landmines. Trying to convince us he was insane.”

But she says for the most part, the sailors were well-behaved.

“The only real trouble I had was one night when I looked out of my office window into the ward, and saw a new patient going up and down the aisles pouring drinks. I told him he couldn’t do that, but he wouldn’t give me his bottle. I had to call for the Chief Petty Officer to take it from him,” she says.

“After that, the sailors started calling me CPO. They weren’t calling me sister anymore.”

Ferguson says the most difficult time working was when HMCS Valleyfield, a large Canadian convoy ship, was torpedoed off the coast of St. John’s.

Over 125 sailors were injured and sent to the Newfoundland base for treatment.

The attack occurred in the middle of the night, coinciding with a practice alarm run occurring at the hospital.

By this stroke of luck, all hospital staff was present when sailors started being delivered.

“We stayed on our feet, day and night,” recalls Ferguson.

She and the other sisters crowded the sailors into already full wards, propping their frost-bitten feet up on pillows.

Almost all of the sailors were diagnosed with immersion foot, a result of prolonged exposure to the frigid seawater.

“I always heard a lot of stories from the sailors, especially at night,” she says.

“Some of them would be troubled, and some of them couldn’t get to sleep, so I would play rummy with them or make them sandwiches.”

“I’m very placid, or I was,” says Ferguson.

“So that really helped in my interactions with them.”

Not long after HMCS Valleyfield was torpedoed, the Canadian government approved the use of penicillin in hospitals.

“I remember being very impressed by it,” she says.

“We couldn’t touch it. A tray would be set up next to the patient for the doctor, and they would mix the yellow powder with sterile water and administer it to the patient. My job was to keep three charts: one for the government, one for the doctor, and one for the hospital.”

Within months, Ferguson says, penicillin’s popularity caught on so fast nurses were administering it in vials themselves.

On their days off, the nursing sisters would visit the American fort nearby, which had nightclubs and dance halls.

“If we were running errands around the town, we were treated just beautifully by the Newfoundland people and welcomed everywhere we went.”

Ferguson recalls one store that would give the nurses a call whenever they got a shipment of nylons.

“Nylons were really hard to get during the war, because their material was needed to help make parachutes, but we were always kept well stocked,” she says.

By 1945, after working two-and-a-half years as a naval nurse, Victory in Europe Day arrived on May 8.

“We heard stories of the sailors rioting in the streets of Halifax, because they had closed the bars,” says Ferguson.

Back at the base hospital, the head matron of the nursing sisters called all the nurses to the main boardroom.

“She said: ‘the war in Europe is over. We’ll have to splice the main brace.’ That meant you had to take a drink of rum,” laughs Ferguson.

The nurses were sent from St. John’s to Halifax, on a cautious, seven-day crossing of the Atlantic in waters with potentially still-active German U-boats.

Ferguson was bound for a Christmas visit to Inverness.

She wound up covering shifts of nurses away for the holidays at the Inverness Hospital, and unintentionally settled in her hometown once again.

After marrying her husband, Hugh Ferguson, the two moved to Detroit where employment prospects looked more promising.

“I went and worked at Grace Hospital there and retired when I was 62,” says Ferguson, who ended up devoting 38 years of her life to nursing. “They took my blood pressure at work one day and told me I was through.”

Rachel Lallouz

Staff writer

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author:

Wow, that is a great biography! this is my friend< Marion's Aunt! she sounds like a great lady! sadly she is no longer with us but I thank my friend for allowing me a peek at a great lady!

I am so proud to call this awesome lady and nurse my friend. Thank you for your service Greet. Your patients were very fortunate in having you provide their care. As a nurse Greet and I have a special connection to St Michaels in Toronto. Greet is a graduate of their school of nursing and I nursed there in 1965.

Hi aunt Greet,I’m going to add this article to the Inverness Legion album”The women from Inverness County who served in the military during War time” Thank you for your service to your countrt Canada.

Dear Greet,

Thank you for sharing a part of history with us. Without hearing stories like yours we cannot know what happened in the past.

I believe you were well suited to the nursing profession. The men and women you nursed were very lucky to have your wonderful spirit, knowledge and beautiful face to help them through terrible times. How wonderful to have had the opportunity to make so many people’s lives less painful and much better.

God Bless you.

Hugs

Janet

Dear Greet,

What a wonderful story! Thank-you for sharing your memories. Your experiences helped to make you the strong, capable and loving person that you are to-day. All of your WW2 patients must have thought they were in heaven when they looked up at you and saw their angel.

Your family including all of your nieces and nephews are all so very proud of you. We thank-you for your courage in helping to serve our country

during the war years. God bless you.