Peter Mallett, Staff Writer

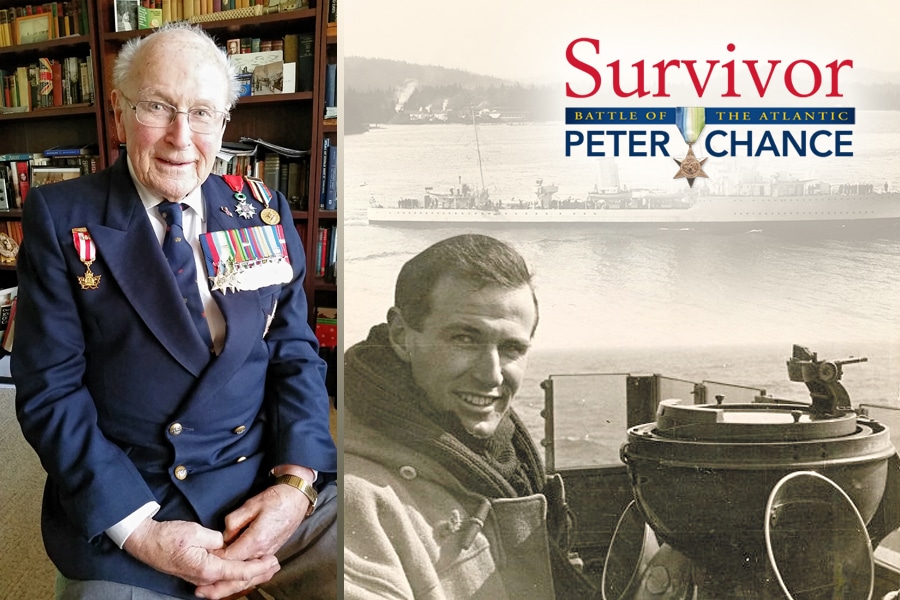

When Retired Commander Peter Chance, 97, addresses the room during the All-Ranks Mess Dinner at the Wardroom May 4, he will relay, through his own stories, what it was like to serve and survive the Battle of the Atlantic.

Pay little heed to his age, or his 30-year career, or the rack of 14 medals on his service jacket. Rather, remember the bygone sailors, honour them, and reflect upon their service to country, and try to relate it to the service of today – that will be his message as he looks upon the crowd of young military members.

The battle on the seas more than 75 years ago was the longest continuous military campaign during the Second World War. The outcome was not assured. But victory was eventually achieved; however, at a huge cost: between 1939 and 1945, 3,500 allied merchant ships and 175 Allied warships were sunk, and some 72,200 allied naval and merchant seamen lost their lives.

“History was not predetermined, and the truth is the Allies were losing the war because the Germans were sinking our merchant ships and vessels faster than we were able to replenish them,” says Chance. “It was purely a question of survival. The Nazi war machine was splendidly efficient. Britain was left by itself, and if we couldn’t hold out it was going to be game over and the Nazis would be supreme.”

For his part in the war, Chance served in a variety of Canadian warships including HMCS Skeena, HMCS Seacliffe, and HMCS Gatineau. They were part of Hunter-killer Groups, also known as Convoy Support Groups, which were anti-submarine warships actively deployed to attack German submarines.

Sailing was dangerous business; below the surface German U-Boats were at the ready to deploy their torpedoes, and Mother Nature was merciless, battering ships with forceful winds that would whip up waves to crash upon the bows, and weigh the decks with thick ice.

One fierce Atlantic storm sent Chance’s ship Skeena aground on Videy Island, near Iceland.

Skeena and three other warships from Escort Group II, tasked to patrol the UK-Iceland Gap for German U-boats, had battled a horrific storm for four days when they decided to take refuge at Reykjavik’s Harbour, near the island.

Wind gusts approached 100 knots, waves swelled 50 feet – the height of a five story building – and snow blinded the crews’ ability to see, but they thought they were safe enough from land when they dropped anchor. They didn’t realize the ship was slowly being dragged inward.

“It was like drawing a spoon through sugar as the ship dragged, filled with water, and went piling onto the shore,” says Chance. “The force of the waves was so great the ship eventually cracked and we had oil mixed with snow on the upper deck.”

Fifteen of his shipmates were killed after boarding a Carley float (life raft) in a failed attempt to evacuate the ship. Chance and the rest of the crew stayed onboard and “hung on.”

“There’s nothing so disarming; everything is exaggerated in the dark of night because you feel so helpless, as indeed we were,” he said. “We just had to pray to God we all weren’t going to perish.

At dawn the next day, landing craft pilot Einar Sigurdson and a team of rescuers braved the weather to run a cable from the ship to land. One by one, the crew was shuttled off the broken warship in a basket.

A few days later, the surviving officers and crew attended the funeral of their lost shipmates.

The ship was raised the following year and eventually broken up.

Chance then joined HMCS Gatineau and stayed with that ship until the war ended in Europe May 7, 1945.

But there was no time to celebrate as he re-enlisted to serve in HMCS Ottawa in the Pacific campaign against Japan, which ended a few months later.

He would see combat again as part of Canada’s support of UN operations in the Korean War. From April 1951 to July 1952 he served aboard tribal-class destroyer HMCS Cayuga, overseeing navigation and air direction during bombardments along the coastline.

Since his retirement from the navy in 1970, Chance served in the Naval Officers Association of Canada, the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Program, and the Royal Canadian Legion for decades. In 1986 he was awarded the Admiral’s Medal and then in 2002 the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal; in 2014 he received the French Legion of Honour Medal at the rank of Knight and was also awarded a Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation.

At the mess dinner on Friday, he hopes to speak one-on-one with the guests, especially those of the junior ranks, to further impart his message – we are all one navy serving Canada – past, present and future.

Stay connected, follow Lookout Navy News:

Facebook: LookoutNewspaperNavyNews

Twitter: @Lookout_news

Instagram: LookoutNavyNews